From NBA Star to HIV Icon: Magic Johnson Changed the Narrative and Revealed Black Reality

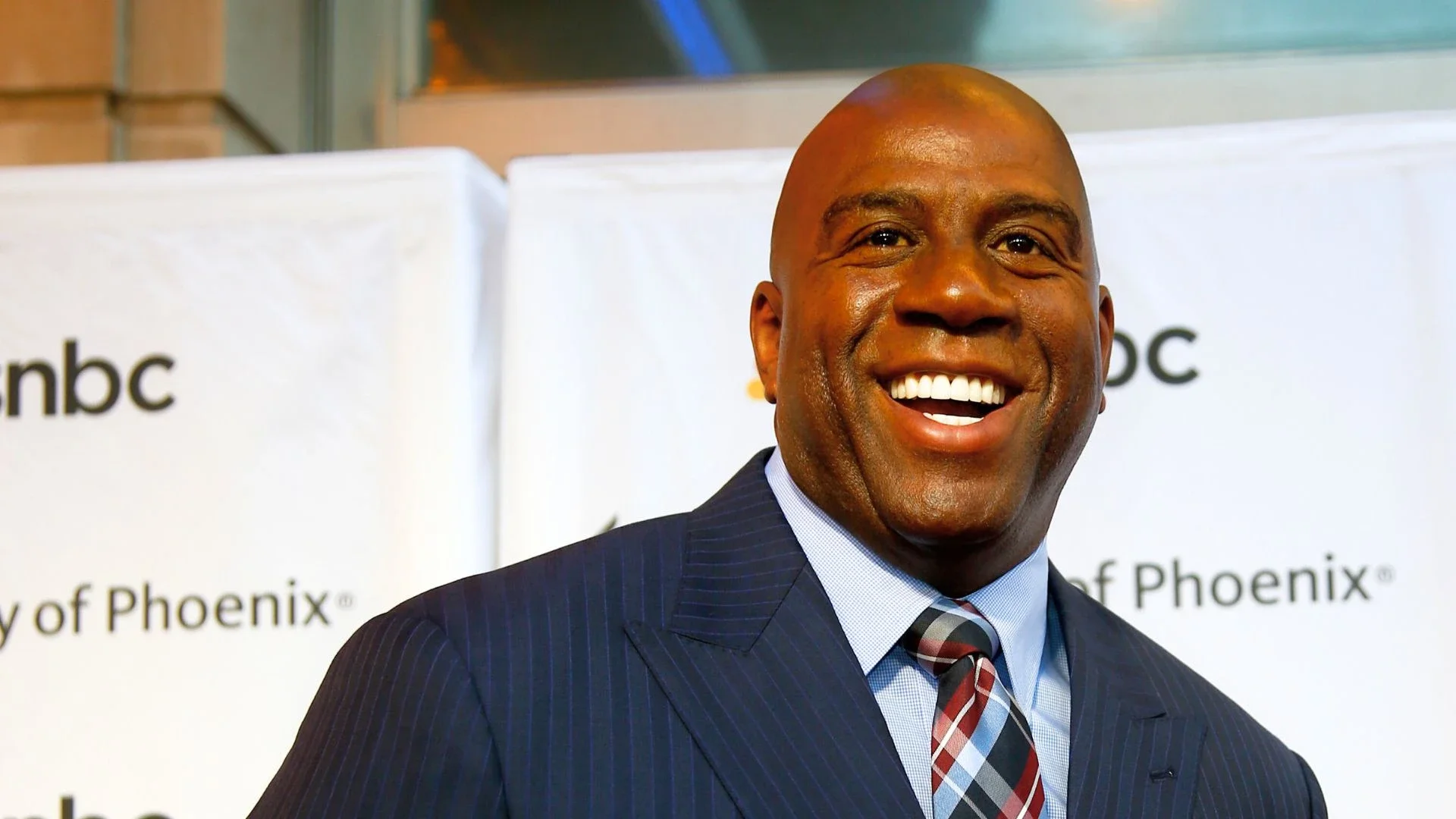

Earvin “Magic” Johnson bounded into a packed luncheon at the National Minority AIDS Council’s annual U.S. Conference on HIV/AIDS in early September like a man who had outrun a prophecy.

Flashing his megawatt smile and practically radiating charisma, Johnson posed for selfies with clusters of people who rushed the stage in Washington, D.C., and jockeyed for his attention. At age 66, in a royal-blue suit, white T-shirt, and sneakers, he looked solid and fit and not at all like someone many assumed would not reach his 35th birthday.

In 1991, Johnson — then one of the greatest pro basketball players in history and a global celebrity — announced he was infected with HIV, the virus that causes AIDS. Since then, he has arguably been the most famous HIV-positive person on the planet, an ambassador for early detection and literally living proof that a once-deadly virus could be conquered.

“God is so good,” Johnson said, beaming, as he grabbed a microphone, stepped down from the stage, and strolled between tables, cellphone cameras following every move. It’s incredible, Johnson said, to reflect on “a moment that changed my life forever.”

Back then, when he told the world he was HIV-positive, there was just one AIDS drug on the market, and the Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis, or PrEP, breakthrough was more than a decade away. Johnson immediately retired from the NBA to start treatment; no one knew how the grind of an 85-game pro basketball season would affect his body. Given what was known in 1991, though, Johnson also sounded like a man trying to convince himself he would survive.

“I plan on going on, living for a long time, bugging you guys, like I always have,” he said in a hastily arranged press conference. “You know, sometimes you're a little naive about it, and you think it could never happen to you. You only thought it could happen to other people, and so on and all. And it has happened, but I'm going to deal with it, and my life will go on.”

Yet it was a transformative moment: AIDS killed some 29,000 people in 1991, and was the leading cause of death among Black men, but news coverage portrayed it as a disease afflicting white gay men in San Francisco clubs and Greenwich Village speakeasies — not NBA locker rooms. Johnson’s disclosure cracked that myth wide open: if Magic, a Black heterosexual sports hero, could get HIV, anyone could.

“The first narrative of HIV was that it was exclusively a white, gay disease,” Phill Wilson, founder of the Black AIDS Institute, told Plus Life Media last year. “Obviously, that narrative was completely wrong.”

“While treatment has transformed HIV from deadly to manageable, Black men are still less likely than white men to get on medication, stay in care, or achieve viral suppression.”

Over time, however, with treatment, self-discipline, and support, Johnson not only survived but thrived; he won an Olympic gold medal with the basketball “Dream Team” in 1992, and his return to the NBA in 1996 was a triumph. But for the millions of Black gay men who still shoulder the epidemic’s heaviest burden, Magic’s longevity is also a reminder: not everyone gets the chance to become a miracle.

Nevertheless, while the cameras followed Johnson’s remarkable journey — and his wealth and fame gave him access to the best treatment and most advanced drugs — whole communities of Black gay and bisexual men were quietly being devastated. Their infection rates in the early 1990s outpaced white gay men’s, driven by poverty, stigma, and sparse access to care. Few outside the Black community noticed.

More than 30 years later, the disparity persists. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says Black gay and bisexual men made up about a third of new HIV diagnoses among men who have sex with men in 2022. Among young Black gay men ages 13 to 24, the rate was more than seven times that of their white peers.

While treatment has transformed HIV from deadly to manageable, Black men are still less likely than white men to get on medication, stay in care, or achieve viral suppression. As of 2022, only about 53% of Black people with HIV had achieved viral suppression like Magic, compared to 63% of white people.

Still, Johnson’s stunning 1991 disclosure forced a national reckoning: testing surged, funding flowed, and suddenly parents who could barely utter the word “condom” were talking to their kids about HIV. Johnson himself launched a personal crusade for change: he visited Black churches, spoke to youth groups, lobbied lawmakers for increased funding and better resources. For a nation steeped in fear, he embodied hope.

“I was able to learn a lot,” he told the luncheon audience. “It was no longer a white gay man's disease. Now it's moving into the black and brown community, but it was harder to get the message out to our people.”

“Johnson’s stunning 1991 disclosure forced a national reckoning: testing surged, funding flowed, and suddenly parents who could barely utter the word ‘condom’ were talking to their kids about HIV.”

To change that narrative, “I would go to a high school first, and I would go, hopefully, to a college, and then I would go to the church at night,” Johnson said. “Once we got them on board, the message got out because, I tell you, our community — boy, we know we got some misinformation. They said, ‘Magic on some magical drugs that we can't get.’ So I had to dismiss that rumor.”

Today, Johnson embodies what’s possible when science and resources align with the relentless drive and discipline of a championship athlete. For decades, he’s had an undetectable viral load — meaning the amount of virus in his blood is so low it can’t be transmitted sexually. The phrase “undetectable equals untransmittable,” or U=U, has become gospel in HIV prevention.

LOS ANGELES - SEP 21: EJ Johnson, Cookie Johnson, Magic Johnson and Family arrives for the Elizabeth Taylor Aids Foundation Benefit on September 21, 2023 (Shutterstock)

Yet advocates note that too many Black gay men don’t reach that milestone. While a former NBA superstar and wealthy businessman like Johnson has access to the best care and cutting-edge treatments, ordinary Black men are less likely to be prescribed PrEP — the daily pill or periodic injection that almost completely blocks HIV transmission — and less likely to stay on treatment if diagnosed.

Johnson, though, didn’t talk about viral loads or drug regimens at the NMAC conference. Instead, he spoke about hope and responsibility. He credited his wife, Cookie Johnson, for standing by him. He marveled at how far treatment has come since the early 1990s and honored those in the audience who have tirelessly fought to save lives. And he urged the audience to keep fighting for the next generation.

“I'm happy to see this ballroom, knowing that we've got so many experts and people who have given their lives to help save somebody else's life,” he said. “They're still in the fight, and we still have a lot of work to do.”

But for Black gay men, living with HIV is about more than clinic visits and taking medication. It’s about surviving stigma, navigating racism, and homophobia. It’s about battling depression and loneliness while holding down jobs and relationships. It’s about staying alive in systems rooted in what the CDC calls “social and structural issues,” such as “HIV stigma, homophobia, discrimination, poverty, and limited access to high-quality health care.”

In other words, systems that weren’t built for them.

“As Johnson celebrates his 66th birthday, his life stands as proof of what’s possible: HIV doesn’t have to be fatal. It can be managed, even outlived. But for many Black gay men, that promise remains unrealized.”

“How I got the news was very abrupt and very impersonal,” said Paul, a Black man who tested HIV-positive in 1987, who told his story on the website positivespin.hiv.gov. “I didn’t know that this was not the norm. The actual diagnosis I got was from a clinical nurse. Her way of delivering it was, ‘Well, I hope you know why you’re here. You have AIDS, and you may want to consider making some final arrangements.’”

Johnson himself saw structural barriers in person while serving on President George H.W. Bush’s National Commission on AIDS in 1992. Representing the commission, he toured a new AIDS hospice in Boston that, remarkably, had dozens of empty beds, even as the disease was sweeping through the city’s Black gay community.

“When I went around the community [and], started talking to the people, they said, ‘Magic, we can't get in because of the red tape. They made it so difficult for us to fill out the paperwork,’” Johnson said. “And I said, ‘Wow — you mean they built it for people living with HIV and AIDS, but they made it hard for them to get into this hospice?’ So I quit on the spot.”

WASHINGTON, DC, USA - Ervin "Magic" Johnson speaks with White House reporters after meeting President Bush regarding AIDS. January 14, 1992 (Shutterstock)

He went on: “I jumped off the Commission and said, ‘I got to do more work in my community and make it hopefully easier for them to get housing,’” because housing and care go hand-in-hand.

Public health experts say the tools to end the epidemic exist: normalize testing, make PrEP free and accessible for all, offer same-day treatment, and invest in housing and mental health. But they also stress centering the voices of Black gay men themselves.

That last part might be the hardest. For decades, the epidemic has been narrated around Black gay men, not by them. Johnson’s journey of survival broke barriers and captivated the nation, but it also cast a long shadow. Changing that means shifting not just resources but narratives, putting the men most affected at the center of the conversation.

As Johnson celebrates his 66th birthday, his life stands as proof of what’s possible: HIV doesn’t have to be fatal. It can be managed, even outlived. But for many Black gay men, that promise remains unrealized.

Until it is, Johnson’s legacy is both a beacon and a challenge — a reminder of how far we’ve come, and how far we still have to go.

Joseph Williams is The Reckoning’s Race & Health Editor. A seasoned journalist, political analyst and essayist, Williams has been published in a wide range of publications, including The New York Times, The Washington Post, Politico, The Boston Globe, The Atlantic, and US News & World Report.

A California native, Williams is a graduate of the University Of Richmond and a former Nieman Fellow at Harvard University. He lives and works in metro Washington, D.C.